October 4, 2015: Bad and good - optical roulette

All text and images Copyright Michael E. Lockwood, all rights reserved.

This

is the 50th installment of "In the Shop", and I am amazed that I have

done that many so far. How time flies. I've been

doing installments less frequently

because I have covered so many topics and issues, but a couple of

mirrors that came in recently for potential refiguring demonstrate what

I see coming into my shop on a somewhat regular basis.

This

is the 50th installment of "In the Shop", and I am amazed that I have

done that many so far. How time flies. I've been

doing installments less frequently

because I have covered so many topics and issues, but a couple of

mirrors that came in recently for potential refiguring demonstrate what

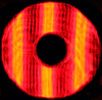

I see coming into my shop on a somewhat regular basis.First, let's look at a poor 4" m.a. secondary mirror from an old 16" telescope. The image at right shows the interference test for this mirror. A quick check of the image with a straight edge shows that one of the fringes bends about 1.5 times the spacing between the fringes, incidating an approximately 3/4-wave error. I didn't even take the time to determine if the mirror was convex or concave because it doesn't really matter - the owner wants a 3.5" secondary anyway, so this one will go back in for polish and will be treated as a blank. I won't even try to refigure it, it will get completely re-worked on a continuous polisher.

When I receive a primary mirror for testing and potential refiguring, many times the first thing that I do is to strip the coating and strain test the mirror. If the mirror has strain, then it may be unsuitable for refiguring because the shape of the mirror may not be stable.

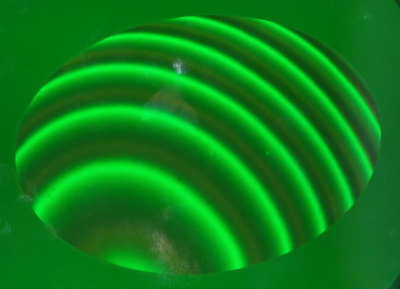

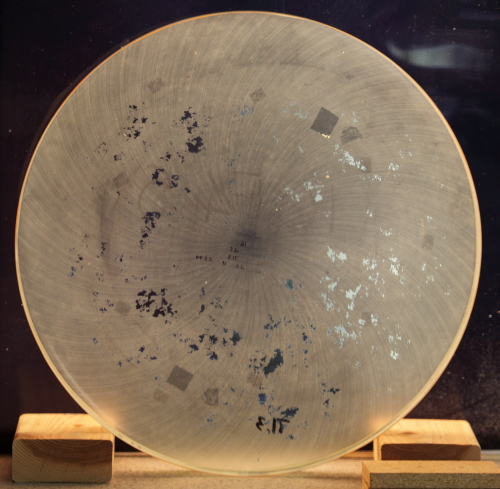

So, next up is the strain test using polarized light for the 16" primary mirror that the flat tested above was intended to be used with. It is a nicely machined Pyrex blank with a machined back surface, and that is a good indication that some care was put into the glass. The news is quite good in this case.

Let me describe

the strain

test image at left.

Let me describe

the strain

test image at left.First, the pattern of arcs, almost like a spirograph, that is faintly visible in the background is simply the shadows from the marks and fractures left by the act of generating the back surface flat with a diamond generating tool. As I write this, these arcs are being removed by grinding the back of this mirror, and I will finish by using 12 micron grit. Doing so leaves a very smooth finish that will slide with very low friction on the Delrin contact points of a custom JP Astrocraft mirror cell with whiffletree edge supports. (As you should know, low friction in mirror cells is what one wants, see my article here.)

Second, the splotchy light areas (at right) and dark areas (at left) are both coating remnants that were stubborn and did not come off with the first application of Ferric Chloride stripping solution. They are bright on the right and dark on the left because of whatever they were reflecting when the photo was taken. Because the mirror will be polished back to a sphere to remove some figure of revolution variations and to improve the quality of polish, I will simply polish off the residual coating when I start my work on it rather than do another round of Ferric Chloride. It is perfectly safe to polish off an aluminum coating, and I have done it many times.

Third, and most important, note the overall background grayness of the blank above - this blank darkened very uniformly as the second polarizer was rotated, indicating an excellent anneal. So, luckily for the owner of this mirror, the anneal is good enough for me to put a superb, stable figure on the glass.

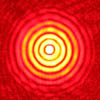

Next up is an old Coulter 17.5" Pyrex mirror that has an owner without quite as much luck. The image at right shows the test results using the same test as for the mirror above, and it is a stark contrast.

The dark "bird" or "airplane" pattern is created because the strain within the glass alters the polarization of the linearly polarized light that passes through it. When this light passes through the second, differently oriented linear polarizer in front of the camera, some of the light is blocked and this creates the brightness variations and pattern. This indicates that there is significant strain in this glass. A roll-off on the back of the mirror is positioned at the top, and this roll-off was obviously the result of cutting the blank out at the edge of a large sheet of Pyrex where the glass always rolls of. That may also explain the orientation of the strain pattern.

Unfortunately,because strain in the glass is like a spring that might cause the mirror to change shape in the future, this mirror will need to be completely re-annealed, ground, polished and figured in order to make it into a good mirror that has a stable figure. While it is possible that the mirror won't change shape in the future if left as is, it is not a risk that I am willing to take, and the owner should not risk their refiguring dollars on it. The back surface has also not been machined flat, and is simply the wavy Pyrex surface that the sheet Pyrex has. Ideally the back would be machined flat and then ground just as the 16" mirror above was.

Currently I also have another old 17.5" Coulter mirror in the refiguring queue, but this one showed much less strain and actually had a fairly good anneal. The back of it was machined flat, and has already been ground to 12 micron against the back of a 24" mirror.

I find that many of the older Newtonian primaries made with nicely machined Pyrex blanks, like the 16" shown above, often are quite good glass. They are often excellent refiguring candidates.

Lately, however, many larger manufacturers have moved to cheaper BK7 or other glasses that may not be annealed at all. This is a bit disturbing, and there is often nothing that I can do with them. I don't want to work on BK7 because it is much softer, and easier to make the surface rough. So, these mirrors will be turned away from my shop because I don't want to waste my time and my clients' money.

The moral of the story is that with certain suppliers and manufacturers, the anneal quality and quality of the glass is simply left up to the luck of the draw. When you buy an older mirror with the intention of having it refigured, you are often playing "telescope roulette".

Mirror owners with unknown glass should discuss this with me before sending a mirror for refiguring. To evaluate the mirror I have to strip the coating, so it is possible you might be left with a bill for testing, a bill for recoating, and a piece of strained glass with an uncertain future.

The moral here is - you get what you pay for - and sometimes you get lucky.

Please check back for future installments of "In the Shop".

Mike Lockwood

Lockwood Custom Optics